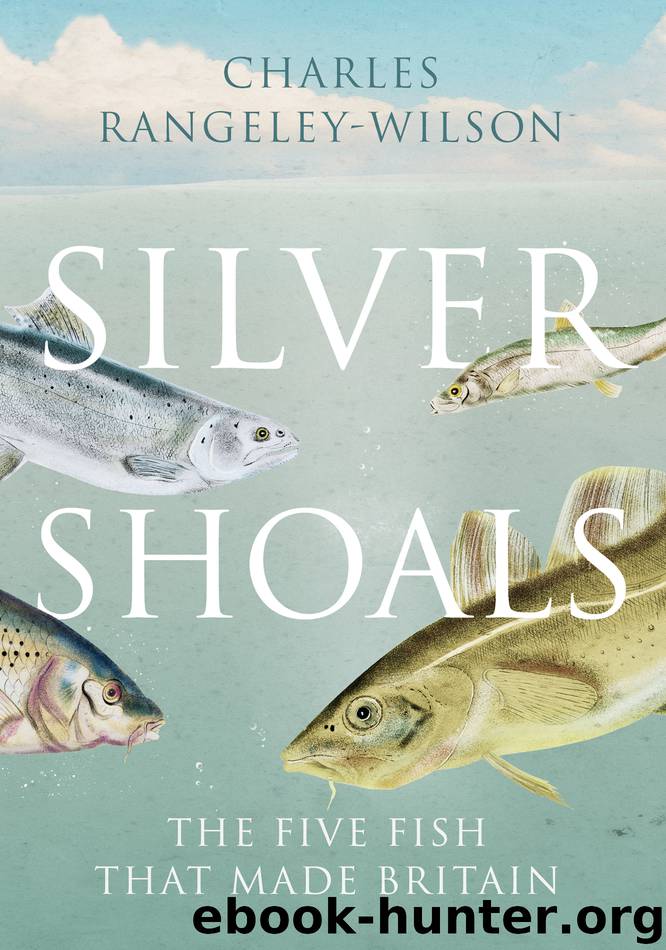

Silver Shoals by Charles Rangeley-Wilson

Author:Charles Rangeley-Wilson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Random House

FISH SILVER

Their stubborn mysteriousness notwithstanding, I wanted to experience eels less vicariously than through my half-baked memories and all these scientific papers I’d been consuming. I wanted to find an eel fisherman who could put me in touch with the wet, slimy reality of them. Like the creature they seek, however, these eel men are a vanishing breed and hard to find. I struggled even though I live in Norfolk, only a few miles from the Fens, the most eelish of places. The cathedral that looms like a sentinel over this flat, once miasmic landscape was built from eels: its stone was traded for vast numbers of this distinctly Fenland harvest. It is named after the eel, too: Ely means eel island. You have to imagine Ely as an island now, but the rise of land is obvious enough, while the waterlogged, willowy corners of the regimented fields and dykes that spread away on all sides are remnants of the flooded swamp that once lapped Ely’s shoreline. These isles – Wisbech, Ramsey, Thorney, Spalding – were the first settlements on the Fens: isolated towns and villages on gentle rises of ground. Their one-time seclusion – which is still palpable – made the Fens a peculiarly English ‘Holy Land’ and on most isles you’ll find a priory, abbey or some other kind of ancient religious house. To every one of these the eel would have been a source of sustenance and wealth.

These isles are surrounded not so much by marsh now as a patchwork sea of drying peat, cross-hatched with dykes and drains, studded with drunken telegraph poles, sagging chimney stacks and windowless pumping stations. The pumping stations are a palimpsest all on their own, in a landscape that is the ultimate palimpsest, like the successively abandoned cottages that surround them, or so many generations of farm tractor you see here and there slumping inside the soil they once tilled. Wind, steam, oil and now electricity have all been used to pump the Fens dry and keep them dry so that nowadays this corner of East Anglia adds up to half of England’s grade-one arable land. Once, the Fens were the least arable place in an otherwise arable kingdom. They were a wild waterland, the accessible edges of which might have been good for the seasonal setting of livestock, but which were otherwise mostly good only for wild-fowling, for cutting reeds and for fishing. The Liber Elienis, a twelfth-century chronicle, describes a Fenscape inhabited by ‘innumerable eels, large water-wolves [pike], pickerel, perch, roach, burbots and lampreys’ – fish in such quantities, echoes William of Malmesbury, ‘as to cause astonishment in strangers, while the natives laugh at their surprise’.

There is hardly a document from the medieval Fens that does not make reference to the fish and fisheries there. The Domesday Book comes alive with the slithering industry of the place. King Edgar’s 974 foundation charter of Ramsey Abbey is wet with the boot prints of its fishermen with their boats and nets, fisher-tenants who paid their rents in ‘fish silver’, namely eels.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Backpacker the Complete Guide to Backpacking by Backpacker Magazine(2234)

Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty(1995)

The Isle of Mull by Terry Marsh(1934)

Predation ID Manual by Kurt Alt(1687)

The Collected Non-Fiction by George Orwell(1598)

Small-Bore Rifles by C. Rodney James(1525)

All Fishermen Are Liars by John Gierach(1473)

Backcountry Bear Basics by Dave Smith(1458)

Creative Confidence by Tom Kelley(1441)

The Art of Throwing by Amante P. Marinas Sr(1385)

50 Famous Firearms You've Got to Own by Rick Hacker(1363)

Blood Mountain by J.T. Warren(1322)

Archery: The Art of Repetition by Simon Needham(1319)

Long Distance Walking in Britain by Damian Hall(1306)

The Scouting Guide to Survival by The Boy Scouts of America(1276)

Backpacker Long Trails by Backpacker Magazine(1266)

The Fair Chase by Philip Dray(1250)

The Real Wolf by Ted B. Lyon & Will N. Graves(1237)

The Ultimate Guide to Home Butchering by Monte Burch(1221)